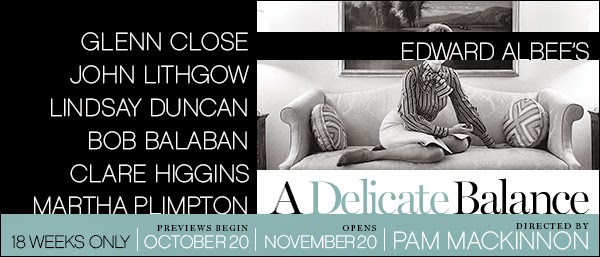

If you didn’t see the 1996 revival of A Delicate

Balance with George Grizzard, Rosemary Harris and Elaine Stritch, then

you will undoubtedly enjoy the current revival with John Lithgow, Glenn Close

and Lindsay Duncan. Close uses the logic of Agnes like a weapon and a shield;

Lithgow embraces the lost, bemused distance of Tobias; Lindsay Duncan (I dare

you to find a syllable of her American accent that isn’t authentic) makes Claire a

lost soul as well as a spirit guide (spirit as in liquor, mostly); and Bob Balaban and Clare Higgins as Harry

and Edna are fabulously offbeat, with Balaban down for a drink one moment and

down the rabbit hole the next, and Higgins making you hate Edna almost

immediately. Only Martha Plimpton as daughter Julia feels like she’s in a

different play. She is all bark and no

bite—literally: she delivers her lines

like a tourist in a foreign country who thinks that speaking English loud enough

will make the natives understand her.

So yes, on its own merits, this production is funny, it’s

sharp, it’s disturbing, and it’s very entertaining. The thing is, the 1996 version was all those things plus

terrifying, which exposed a level in the play that is only glimpsed in one or

two moments in this production.

What’s this production missing? I think of it as the Undertoad.

(And thanks for embedding that one in my brain 36 years

ago, John Irving.) In this play,

there’s a crack in the ice that everyone ignores. Agnes skates around it, Claire drinks so she won’t see it (and

then drinks some more so she can get the courage to jump up and down on it),

daughter Julia gets married to run away from it, Harry and Edna acknowledge it,

and Tobias goes along to get around it.

Without that crack in the ice, the play runs the risk of being a glib

comedy of bad manners, with a lot of laughs that should be nervous and add to

the tension, instead of being, well, comforting. And Tobias becomes a henpecked hubbie instead of someone who’s so

afraid of thin ice that he measures and weighs every step he takes. And because Lithgow doesn’t do that, there’s

no sense of the lava in Tobias that causes his eruption in Act Three.

Also (and I don’t think there’s a word for this, so let’s

call it hop scotching) a lot of the time, the actors are moving before they’re

grounded—reacting before they’ve taken in the thing they’re reacting to. If this was music, they’d be coming in

before the downbeat, and with the same off-tempo result. The strong moments are weakened and

diminished because characters are acting out the results of a decision that is

skipped over—they’re hop scotching over the moment when they take in the fact

that they’ve been attacked or questioned or defeated, a moment they have to

acknowledge before responding to it or else there’s no gravity behind anything

they do.

The only one not guilty of this is Lindsay Duncan, who

spends a great deal of this production living in and reacting to a deeper

version of the play than is presented onstage.

Her reactions retroactively raise the bar on everything that’s going on.

But never to the level of the bar that was

set by the 1996 revival.

So if you never saw that revival, go see this one.

And if you did see that revival, go see this one

as well—because it will, by what is absent in it, reinforce everything that made

the 1996 revival a classic.

No comments:

Post a Comment